The 7 Most Common (And Painfully Annoying) Medical Mistakes in Movies

As time goes by and information travels faster, movies steadily improve their accuracy.

Yet, there are still some mistakes made time and time again, especially in medicine.

1. When an object is embedded in the skin…

Don’t pull it out! Don’t! Especially if you may make it to a medical professional in the near future.

The recommendation is that you bandage heavily on either side of the embedded object (in a rolled-up “donut” or triangular shape). Apply pressure as best as you can without pushing it further in. If it’s a small splinter that hasn’t gone far in, you can pull it out with sterile tweezers in the same direction that it came in to prevent further damage to the tissue.

Of course, many protagonists don’t have time for that, so they just yank out the object. You’re not supposed to do this because of the further damage you could cause to the tissue. When you’ve been stabbed by something, whatever it may be, you don’t know where it’s lodged or if it’s stemming any bleeding—because of this, pulling it out could also kill you.

2. Gunshot wounds

When it comes to gunshot wounds, there are quite a few things that movies get inaccurate:

Hello? It’s me, the exit wound

When someone gets shot in a movie, we immediately know what has happened based on the large volumes of blood gushing out of the entry wound. Yet, exit wounds bleed a hell of a lot more than entry wounds. They’re larger and a lot gorier due to the bits of damaged muscle and skin peeking out of them.

Although this mistake is less common, it still happens nowadays: the entry wound either bleeds more than the exit wound, or there is no blood at the exit wound.

You don’t need to extract the bullet straight away

Movies tend to have this obsession with getting the bullet out of the character’s body. In reality, many gunshot victims still have the bullet or bullet fragments lodged inside them years after the incident.

Some recent studies have shown that bullets can cause lead poisoning and other issues (e.g. infection), but medical professionals don’t take it out unless it becomes problematic. Taking it out without an immediate need could cause more damage and harm the patient further.

And anyway, extracting bullets isn’t that easy

It’s the typical makeshift surgery scene: An uncannily attractive person in a car or a boat or some other unsanitary environment. This person has been shot. They proceed to dig into the wound (using tools that are definitely not sterile) to find the bullet. They find it and take it out.

End scene.

But here’s the thing: Our illustrious attractive person might not find the bullet. Because of the nature of a gunshot wound, the bullet could’ve ricocheted far away from the entry point.

When medical professionals treat any emergency, they always check the entire patient’s body for any injuries they could’ve missed. But this is especially true for gunshot wounds, as the bullet could’ve entered someone’s thoracic cavity and exited via their foot!

So although movies don’t necessarily get this wrong, it’s uncanny how many characters extract bullets within seconds, without any problems.

Also, depending on the gun and the range at which it was shot, sometimes the bullet’s heat cauterizes the entry wound. Again: our illustrious attractive person would be having a pretty hard time digging out that bullet.

3. Tourniquets

These are used as a last resort, not as standard practice. Luckily, modern movies have mostly stopped using these, but it was used frequently in films about a decade or two ago.

A tourniquet is a device used to stop the blood flow to a limb by constricting that limb and cutting its circulation. Usually, you will see it in movies as a bandage rigged up to a stick. The stick is twisted, and the dressing twists with it, tightening around the limb.

Although this was commonly used in the 1900s (especially on soldiers during wartime), we use it today only when necessary. By restricting the blood flow, you can damage the tissue in the limb permanently.

4. Hair and hands, people!

You can’t do an autopsy or a surgery without being covered up.

That includes hair. Movies always feature characters who have their hair loose and free to rub all over the patients.

And then they’ll go touching dead bodies with their bare hands.

That’s just-

It’s-

It’s disgusting.

If you don’t want diseases and infections to spread, the number one thing to consider is hygiene, especially in a medical environment.

Gloves, hair caps, even masks — those all exist for a reason. No self-respecting nurse or doctor would go around touching people (and certainly not sick or dead ones) without gloves.

But alas, Hollywood has yet to remedy this inaccuracy.

5. Administering medication intravenously

For some reason, movie characters seem to think that stabbing a needle into someone at a 90-degree-angle is a great way to go about administering drugs. Especially in the chest, which even trained medical professionals don’t do unless necessary. If you try to deliver directly to the heart, there are many ways in which you could puncture a lung or an essential blood vessel.

In most cases, with drugs like epinephrine (adrenaline), it’ll probably be through the veins in the wrist if administered intravenously. If it’s an intramuscular injection, it’ll probably be through the thigh.

And the ideal site of injection, especially when a large amount of fluids is being administered, is the antecubital fossa. If you’ve ever gone for a blood draw, the doctor most likely drew from there — right where your inner elbow is. The three blood vessels there (cephalic, basilic, and median cubital) are preferred because of their size and how easy it is to find them.

So no, please don’t go around stabbing people with needles.

6. Resuscitation

Boy, this one is a doozy.

Let’s start with:

The speed and ratio of compressions to breaths is waaaaaay off

Yup. In most movies, characters average 3–5 compressions for every 1–2 breaths. In reality, it’s supposed to be about 30 compressions for every 2 breaths.

On top of that, characters do CPR at a lot slower rate than in real life. Ideally, CPR should be done between 100–120 bpm. Songs like “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees at 104 bpm or “Another One Bites the Dust” by Queen (ironic, but it works) at 112 bpm are in this range. Studies indicate that going above 125 bpm will decrease effectiveness, but it’s usually in your favor to go faster rather than slower when in doubt.

With that said, pretty much all revival scenes are inaccurate, and that’s without me getting to my next point.

Resuscitation takes much longer than shown

Most movies featuring a resuscitation scene go something like this:

The patient collapses. The character attempting the resuscitation starts reviving the patient but gives up after a couple of minutes. After a few moments of tense silence, the patient gasps and splutters awake.

In reality, that doesn’t happen. Reviving a patient can take hours of back-breaking, nerve-wracking work, and every second counts. Giving up after just a couple of minutes significantly reduces the patient’s chances of survival.

And obviously, the patient regaining consciousness is not the only indicator of them being alive. Pronouncing someone as dead is a lot more complicated than it seems and involves many factors. Always continue to revive someone even if they appear to be dead because the chances are that’s the only thing keeping them alive.

7. Most mental illness, because let’s be real here

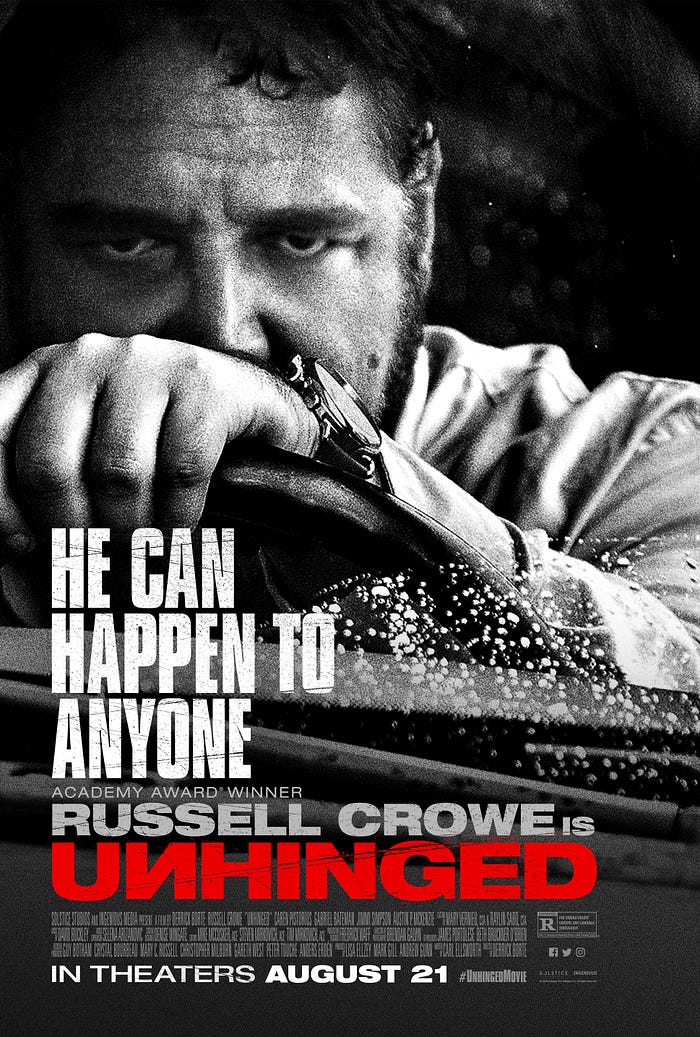

I recently watched a movie called “Unhinged.”

It’s a pretty simple plot. Russell Crowe plays our unnamed, “unhinged” villain, who violently pursues the protagonist Rachel Hunter (played by Caren Pistorius) following an encounter at a red light. But after watching it, my sister mentioned a problem with the movie: the portrayal of mental illness.

Our antagonist is never named. We just refer to him as “The Man.” We know nothing about him. He’s a completely static character. And that’s okay: I have nothing against static villains.

But this guy is also popping prescription pills like crazy throughout the movie. We know he’s been diagnosed with some illness, and we naturally assume it isn’t physical.

The association goes something like this:

Prescription = Doctors = “Mental” Patient = Criminal

We see this depiction of the “crazy” or “disturbed” villain in so many movies, even though most people with mental health issues can live relatively normal lives. John Hopkins Medicine reports that 1 in 4 American adults have at least one diagnosable mental disorder in a given year.

But because of the entertainment value of having the “psychos” and “schizoids” as the villains, the stigmatization of mental illness in films is still a big problem today.

This is especially true in horror movies. You can find examples everywhere: Take a movie like Split or a character like Harley Quinn. You’ll see exactly where I’m coming from.

In some books, we are slowly seeing this stigma fade away, but movies have yet to catch up.

Many of our ideas and biases come from the media around us. Movies included. But we rarely ever notice the inaccuracies in them.

So next time you watch a movie, look out for these seven mistakes. You’ll find they’re a lot more common than you think.